The newly appointed US secretary of defence, Pete Hegseth, made his inaugural speech to NATO and European allies at a Defence Ministerial on February 12. As a Trump loyalist, he conveyed his forthright message to an august audience. His speech was received in stony silence by grim-faced European officials and politicians.

Exhibit 1: Hegseth speaks to NATO allies…

His proclamations portend a major rupture in the transatlantic alliance that has endured since the 1950s. Thus:

- European security should be the sole responsibility of Europe

- Rich European countries should not expect the US to continue to act as Europe’s security guarantor through NATO

- These countries should aim to spend 5% of GDP on defence even if the US does not.

- The priorities of USA lay in Asia and in securing its own borders against millions of illegal migrants seeking to enter the USA from South America.

Perhaps the most conspicuous statements by Hegseth pertained to the way the US perceives the future of Ukraine.

Thus:

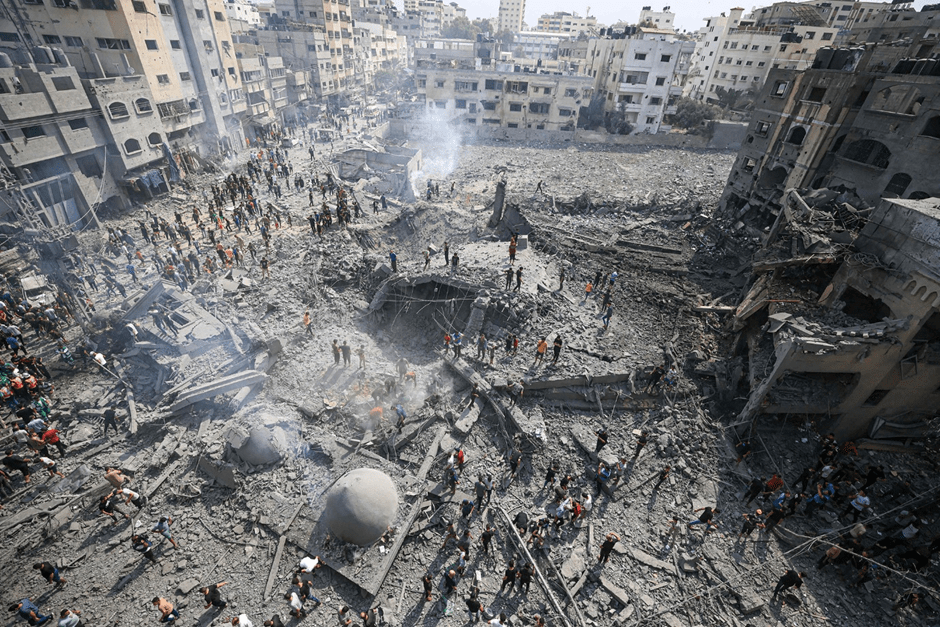

- It is unrealistic to expect Ukraine – and Europe at large – to return to ‘pre-2014 borders’, that is, Russia can expect to retain Crimea and probably the vast bulk of Ukrainian territory that it has acquired since the Russo-Ukraine war that started on February 24, 2022

- It is unrealistic to expect Ukraine to become a member of NATO.

- Any ceasefire agreement between Russia and Ukraine would have to be monitored by European and non-European troops – but not NATO and certainly not by the USA.

There were understandably adverse reactions from Europe, although the British Defence Minister, evoking the long-standing British tradition of understatement, simply said to Hegseth, ‘we hear you’.

President Zelenskyy was clearly crestfallen but put on a brave face. This did not restrain the editor of the Kyiv Post from lamenting that God Bless ‘America,’ but God Help Ukraine and Europe Fend for Themselves!

European and Ukrainian fears were exacerbated when Trump held a telephone discussion for 90 minutes with Putin. Both leaders agreed that they should meet at a summit in Saudi Arabia where they would finalize the contours of a ceasefire plan that clearly favoured Russia. The embattled Zelenskyy was given a consolation prize by receiving Trump’s post-Putin courtesy phone call.

Exhibit 2: Trump and Putin talkfest

Trump sought from Ukraine a formal agreement to gain preferential access to its rich mineral deposits which he saw as richly deserved compensation for the billions that the USA poured into Ukraine to fight Russia.

Trump also noted that Putin was right to raise concerns about Ukraine not joining NATO as far back as 2007. He felt that Russia should be part of the G7.

Russo-phobic European leaders were apoplectic but there was little that they could do to stop the Trump juggernaut on the ‘America First’ foreign policy that was taking shape in front of their disbelieving eyes. What happened, they wondered, to commitments by the previous US administration that said that Ukraine was on an ‘irreversible’ path to NATO membership? What happened to Biden’s promise that Ukraine would receive its unconditional support and poured billions into sustaining its proxy war against Russia even during the dying days of his administration?

The US Vice President, JD Vance, went even further than Trump and Hegseth. He noted that an enormous and probably unbridgeable chasm has opened between Europe and USA. It was a clash of views and values about the world at large. Unless centrist politicians in the region respected views and voices of American, MAGA-inspired nationalism in Europe, America had nothing to do with Europe. To Vance and fellow travellers, the far-right AfD in Germany was worthy of an audience but not Olaf Scholz, the beleaguered German chancellor. He and his entourage did not even bother to listen to speeches by French President Macron and the EU president Ursula Von der Leyen.

Exhibit 3: Vance issues a stern lecture to European leaders….

It is remarkable that, in the space of a few days, the Trump administration appears to have reconfigured the basic tenets of the transatlantic alliance that was consolidated during the Cold War. It is pathetic to watch Zelenskyy take on the mantle of European leadership. He made the delusional proclamation of forming a formidable European army in which Ukraine would play a pivotal role to deter Russian aggression in the absence of any tangible support from USA.

The harsh reality is that the European leaders allowed themselves to become subservient to the US and simply followed the Russo phobic policy of previous US administrations that reached its zenith under Biden. They tried hard to cling to the fantasy that Russia really does not belong to Europe and that it ought to be isolated and defeated diplomatically economically and militarily even if it means pouring billions into broken nation like Ukraine – billions that could have been spent on the welfare of European citizens. Along comes someone like Trump and ruptures such a fantasy.