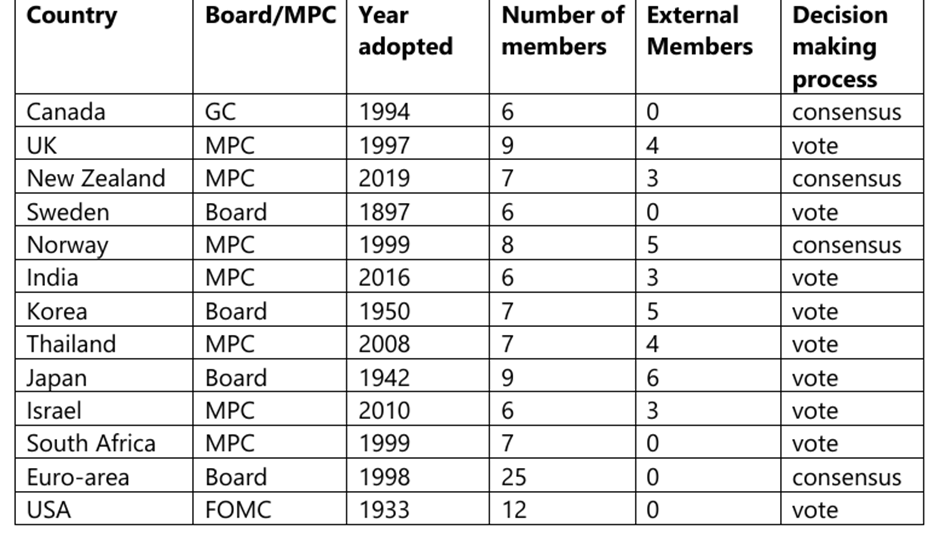

Source: Financial Times

President Trump and his loyalists are true believers in the omnipotence of tariffs. They believe such taxes on imports will deliver economic nirvana to Americans. Tariff-jumping companies – both of US parentage and beyond – will return to US shores to jump-start manufacturing and create much-needed jobs, especially for the residents of the American ‘red states’. Revenues from higher tariffs will fill the coffers of the Treasury enabling Trump to engage in pork-barrelling and funding pro-rich tax cuts.

Trump and his acolytes despise bilateral trade deficits. Such deficits reflect an underlying malaise: tthe rest of the world is allegedly ‘ripping off’ the US. Hence, the idea is to ‘carpet bomb’ hundreds of countries with punitive tariffs with China becoming a particular target of opprobrium. The global effective tariff rate is now the highest in the world since the turn of the 20th century.

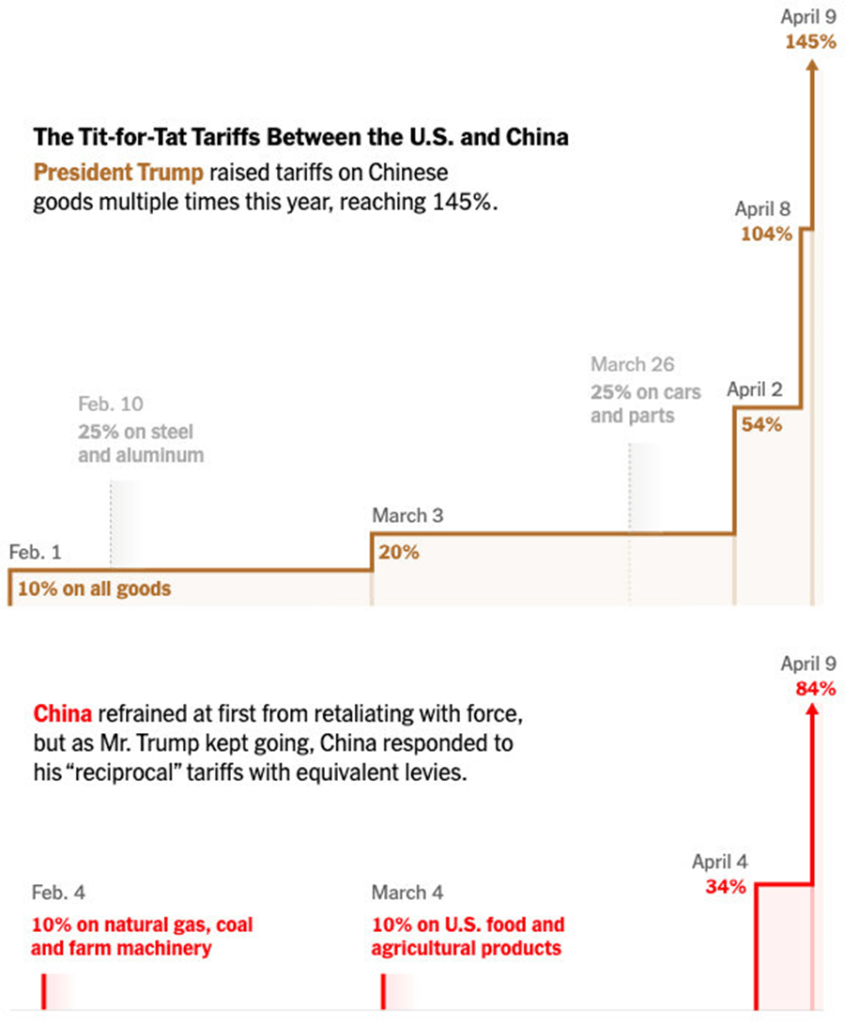

While countries such as Vietnam have capitulated by offering to implement zero tariffs on American goods and services, and while some long-term allies, such as Australia, have offered no retaliation, China has taken a different approach. It has engaged in an active trade war with the USA by imposing retaliatory tariffs – see Exhibit 1 – and has announced complementary restrictions on American companies doing business with China.

Exhibit 1

Source: New York Times, 11 April, 2025

Which party will prevail in this clash of two titans of global commerce? To start with, Trump has blinked, despite his asinine proclamation that various countries of the world are prepared to ‘kiss his ass’. (warning: distasteful video content). He has been humbled by developments in global financial and bond markets. Stock market prices have declined sharply in response to the Trump tariffs. More importantly, one detects a restive bond market with returns on long-term US Treasury bonds rising sharply to 5 percent.

This has ominous implications for US borrowing costs as well as the cost of financing sovereign bonds in other parts of the world. Trump was forced to engage in strategic retreat by imposing a ’90 day’ pause on tariffs worldwide with the conspicuous exception of China. But…the Chinese authorities must have noted, in common with others across the world, that Trump’s seemingly invincible aura has been tarnished.

Furthermore, many of the supposed benefits of the Trump tariffs represent wishful thinking rather than a pragmatic assessment of likely outcomes. Thus, the idea of tariff-jumping companies relocating to the USA is far-fetched, given that this is a process that takes time and relies on a predictable tariff regime. Trump has shown that the trajectory of tariffs under his regime will be highly erratic shifting with shifting economic and political circumstances.

The notion that tariffs will yield a revenue bonanza for the US government also ignores empirical regularities. Many decades ago, economist Arthur Laffer discovered the Laffer curve on the tax-revenue relationship: very low taxes lead to very low revenue collection, but very high taxes also have the same result. The Laffer curve is valid for the tariff-revenue relationship as well. At current prohibitive rates, the Trump tariffs are unlikely to yield a revenue bonanza – see Exhibit 2 – as the ‘volume effect’ of import compression will more than likely offset the ‘value effect’ of higher import duties.

Exhibit 2

Source: https://asiatimes.com/2025/03/tariffs-have-a-laffer-curve-too/

Once again, the Chinese authorities are likely to conclude that the incidence of the Laffer curve will prevent the Trump administration from building a war chest that it can draw on in its trade war with China.

Other factors at play put China at a strategic advantage vis-a-vis the USA.

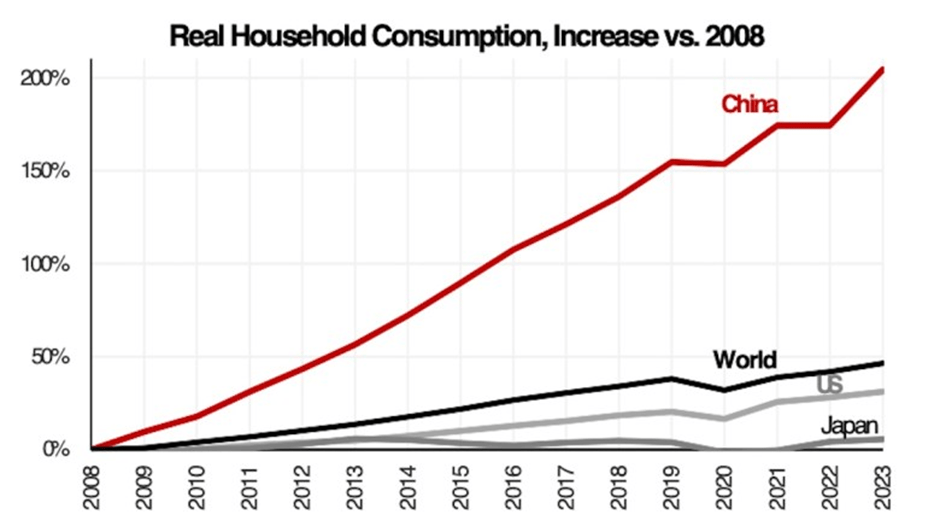

China is no longer a country populated by ‘peasants’ as the American Vice President JD Vance would like to believe. It is now at the forefront of new technologies, ranging across renewable energy, electric cars, robotics, and AI. It no longer relies on cheap imports flooding the US market. Thus, China has undertaken both product and market diversification of its exports. In any case, China has a vast domestic market in which consumption growth is now the highest in the world led by millions of millenials – see Exhibit 3a. This deflates the oft-noted view that the overly centralized Chinese economic system over-invests and under-consumes. China is certainly politically centralized, but this is combined with a radically decentralized economic system that operates at the mayoral level. This is the ‘new China playbook’. (see Exhibit 3b)

Exhibit 3a and 3b–Consumption growth and the new China playbook

China also has a tight grip on rare earth minerals that are critical to the US tech and defense industries. One must not forget too that Elon Musk – the richest man in the world and one of Trump’s main supporters – has heavily invested in China to produce and export Tesla EVs. China, if it really wanted to be mean-spirited, could exploit these US-specific vulnerabilities.

China, as Mahbubani often points out, is the ‘oldest continuous civilization’. Deeply held notions of national humiliation by Western powers in the past (1840-1949) have shaped China’s outlook on contemporary international relations. A civilization is unlikely to be upstaged by an upstart Western power.

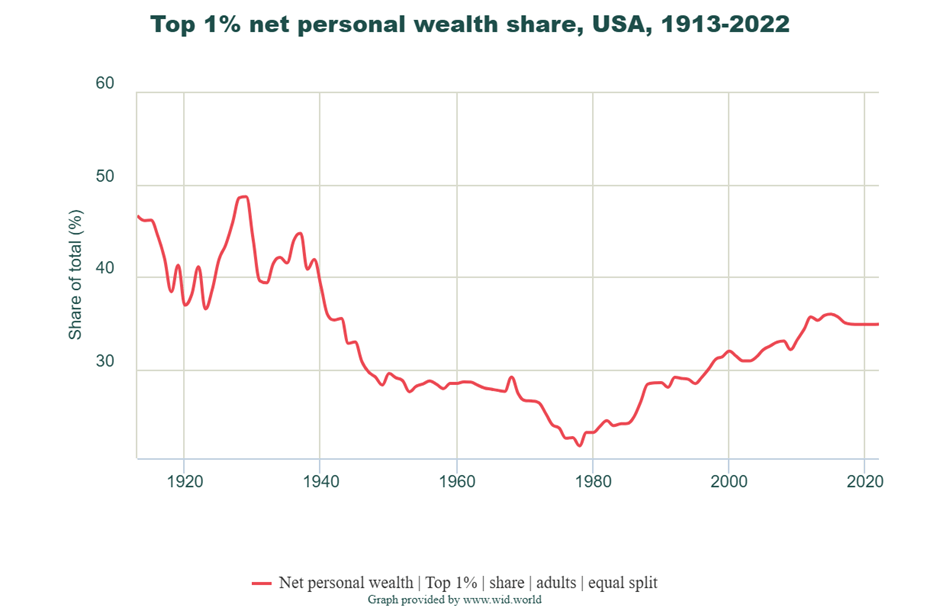

One should not, of course, paint a rosy picture in which China wins, and the USA loses in this trade war. Both countries will have bloody noses and will suffer a great deal of pain, as the Yale Budget Lab points out. Other model-driven estimates suggest that the USA will suffer more socio-economic losses relative to China – see Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 4

A US-China trade war will unfortunately impose considerable collateral damage to the rest of the world. Low- and middle-income countries are likely to suffer the most and will become the victims of this US-led, self-inflicted damage to a rules-based global trading system. Even worse, the putative trade war could lead to a catastrophic conflict on a global scale.