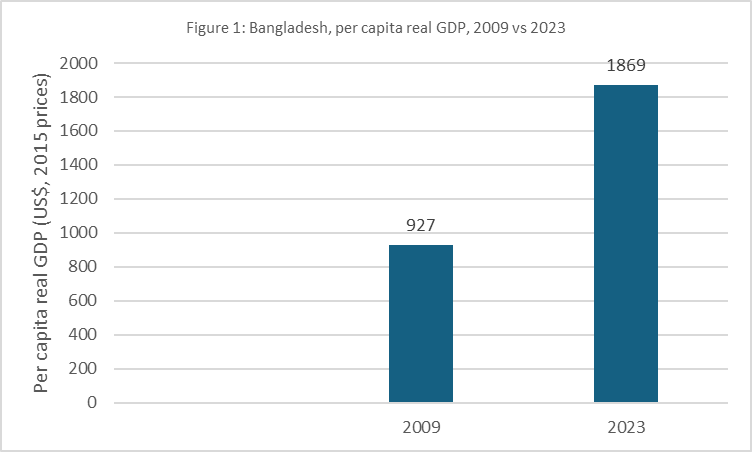

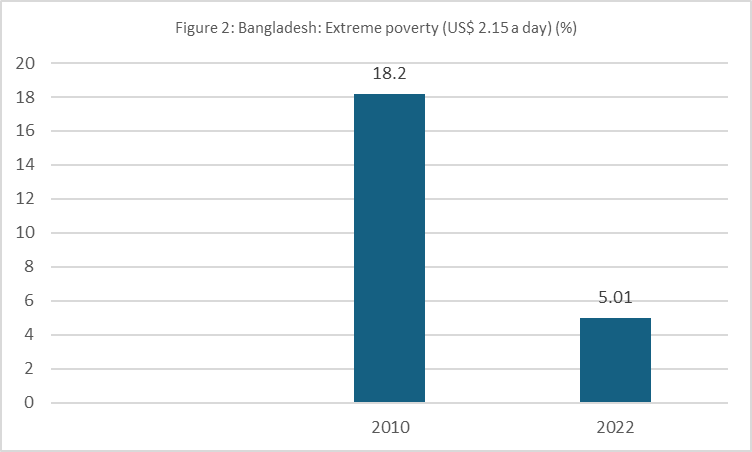

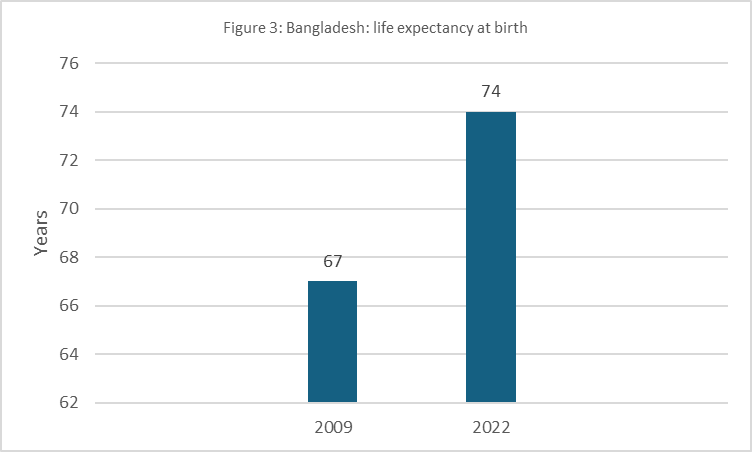

In reporting on financial and economic statistics, it is important to distinguish between stocks and flows as well relative and absolute numbers. Stocks (accumulated value of a variable over a given period) typically catches public attention in a way that annualised data usually do not. Similarly, relative figures usually turn out to be a lot more modest than absolute numbers. I will illustrate these points by drawing on the Bangladesh experience.

In Bangladesh, media reports conflate typically stocks and flows. The currently popular citation is that US$ 150 billion has been siphoned off to various overseas havens by politically connected individuals over the last 15 years. Some media reports proceed to express stock estimates of money laundering as a proportion of flow data (annual GDP). This can befuddle the lay reader.

The task of tracking money laundering falls on the Bangladesh Financial Intelligence Unit (BFIU). I suspect, it is a small, under-resourced unit within the Bangladesh Bank (the best talent and resources probably go to units dealing with monetary policy). This does not make BFIU estimates less reliable than other estimates, but alternative estimates of annual rates of money laundering do exist and they ought to be acknowledged in public discourse. Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) in the recent past has come up with an annualised figure of USD 3 billion, while the Washington-based Global Financial Integrity Institute (GFI) reported annualised figures of USD 8.7 billion. They note that most money laundering activities occur through trade mis-invoicing. One should not also overlook the use of the humble, but time-honoured, Hundi, as a source of money laundering. The bank heist by one of Bangladesh’s richest men is sensational but not a very common source of money laundering.

I personally prefer the use of annualised figure because they are easy to compare over time and across countries. Also, stock estimates can be made to assume astronomical magnitudes. For example, I understand that some Bangladeshi economists have come up with a stock estimate of money laundering for the 1972-2022 period. This understandably dwarfs the size of money laundering that are being reported now.

There is the issue of relative vs absolute numbers. Annualised data on money laundering can be expressed as a proportion of a country’s GDP. This is what the UN does. Another advantage is that this relative number offers an indication of the potential output loss from money laundering. In the case Bangladesh, a back-of-the envelope estimate (which is based on the annualised estimate of USD150 billion) suggests that it is 3.2% of GDP. The global norm ranges between 2-5% of GDP.

Has the incidence of money laundering has gotten worse over time? Here, the changes in country-specific ranking anchored in an ‘anti-money laundering index’ for 152 countries by a Swiss organisation, can be useful (1= worst, 152= best). BD ranked 82 in 2017, but then fell below 40 in later years before recovering to 46 in 2023. Why this has happened merits further investigation.

Finally, it is worth noting that, however measured, money laundering represents massive waste of resources enriching some at the expense of poorer nations. To be resolved, it needs global cooperation. Why is it that Singapore and London, for example, allow themselves to become havens for laundered funds? Indeed, London has been described as …’the main nerve centre of the darker global offshore system that hides and guards the world’s stolen wealth’. If the authorities there camp down on such havens (which they can), the incentive to park illicit funds abroad by crooks and criminals from developing countries will be significantly diminished.