Sheikh Hasina, the longest serving Prime Minister of Bangladesh, and the longest serving female Prime Minister in the world, could not defy the ‘iron law’ of history. Iron law? Yes, all political regimes have a finite time-span.

Hasina ruled Bangladesh with an iron fist. Her security forces – enabled by a pliant judiciary and media – engaged in brutal repression of opposition politicians (Bangladesh National Party and Jamaat in particular) and suppressed any significant attempt at dissent by civic activists, students, and others. Over a period of 15 years (2009-2024), the 76 years old veteran politician built a ‘deep state’ teeming with party loyalists (that is, those affiliated with the Awami League: AL). Her governance structure appeared to be a seemingly impregnable fortress that sustained Hasina’s hold on the body politic. A succession of brazenly rigged elections ensured that she would return to power again and again. Yet, a short-lived movement led by students toppled this fortress like a sandcastle on August 5, 2024. The armed forces on which Hasina relied for her ability to cling to power refused to offer their unconditional allegiance in the face of an unrelenting student movement. Hasina fled in disgrace to neighbouring India which offered her sanctuary, at least temporarily.

Initially, the protest movement targeted a contentious job reservation scheme in the public sector. This scheme disproportionately favoured the descendants of those who fought in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. Such a scheme was in essence a pernicious means to induct loyalists into the bureaucracy.

Tragically, the youth-led uprising against the Hasina regime led to many hundreds of deaths of innocent students and civilians at the hands of security forces and government-supported vigilantes. Thousands were injured and many thousands were incarcerated. Students stood firm against such repression and successfully sought Hasina’s resignation once the army abandoned its support to the government.

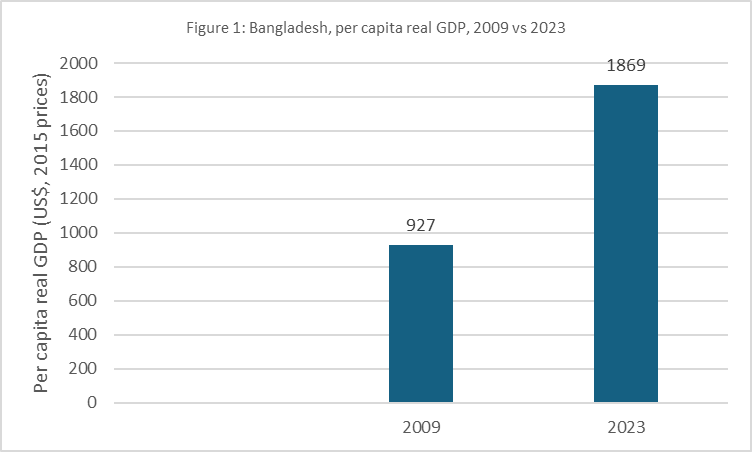

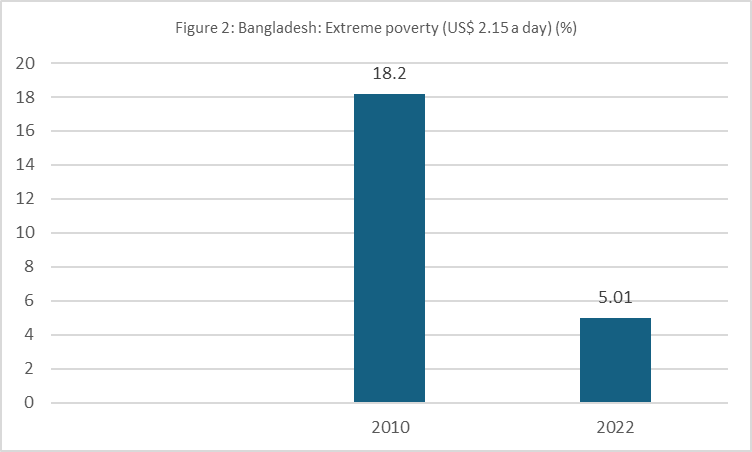

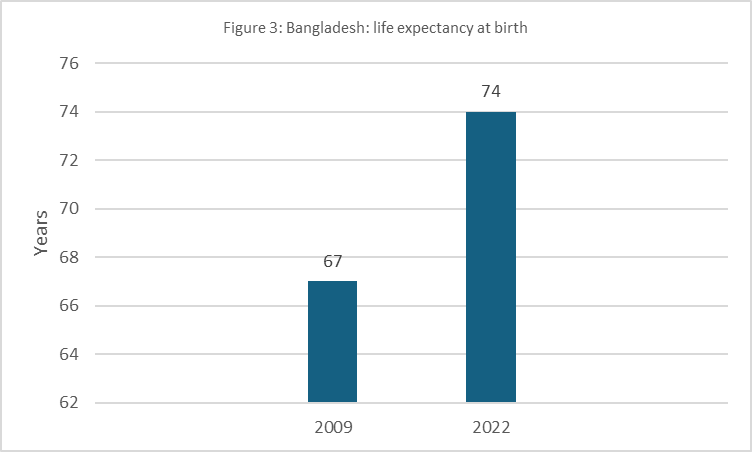

In retrospect, the Hasina regime represents a cruel paradox. Political repression was juxtaposed with substantial economic and social gains. Growth was sustained and rapid leading to a doubling of real per capita income between 2009 and 2023 – see Figure 1. Poverty fell significantly, and life expectancy increased substantially – see Figures 2 and 3. A UN assessment noted that ‘the country is internationally recognized for its good progress on several gender indicators’. The garments industry and remittances consolidated their position as leading export earners. New industries emerged, most notably pharmaceuticals and shipbuilding. Large-scale infrastructure projects were completed that enhanced communications and connectivity.

Source: https://pip.worldbank.org/country-profiles/BGD

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/country/bangladesh

On the other hand, such achievements were nullified by massive corruption, egregious levels of inequality, and environmental degradation. The fundamental failure of the Hasina regime is that it dented the legitimacy of durable economic and social gains by denying Bangladeshis basic rights and liberties, including the right to vote in free and fair elections.

Hasina was also seen as being beholden to India. This caused public resentment at India’s influence on Bangladesh’s national affairs. Her attempt at a balancing act by wooing China was insufficient to dispel the widely held notion that she was slavishly pro-Indian.

Now that Hasina is gone, what next? An interim government, consisting of seventeen members and headed by Nobel Laureate Mohammad Yunus, has been established. It has taken the historically unprecedented step of appointing two student leaders as part of the government with full ministerial rank.

It seems that an implicit rift has developed between the Army brass, the student leaders and professional politicians represented by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Jamaat. The Army Chief and his enablers wanted to form an interim government that that did not include Yunus. The student leaders did not approve of such a move and offered their alternative configuration of an interim government headed by Yunus and one that is politically neutral. They envisage an interim government that will run for a substantial period to complete its tasks and then ensure the holding of free and fair elections. So far, neither the tenure of the interim government nor its terms reference have been made explicit.

For now, the student leaders have prevailed because they have enormous street power, but they – and the interim government that they helped create – face monumental challenges: restoring law and order, reforming the governance structure, restarting an economy that effectively became moribund during the massive disruptions caused by the student-led movement and holding free and fair elections. These challenges are occurring against a background of high expectations about a bright future.

The BNP-Jamaat alliance meanwhile is getting impatient. More importantly, they would like the interim government to hold elections within three months – a time-frame that is unlikely to be accepted by the student leaders. The silent rift among the key actors will then become explicit.

One can understand why the BNP-Jamaat is so impatient. They have an electoral opportunity that they did not believe would ever occur. Their arch nemesis AL is thoroughly vanquished, at least for now. The BNP-Jamaat forces can romp home electorally. What will the student leaders do then?

There is growing realization that the real battle for the future of a new, inclusive Bangladesh has just started. The progressive forces unleashed by the youth-led uprising need to evolve into a new party that can prevail electorally over the old guard represented by professional politicians.

The two dominant parties (BNP and AL), backed by minor allies, have in the past accounted for more than 80 percent of votes cast in relatively free and fair elections (such as 2001). Sadly, they harbour a ‘legacy of blood’ that has tainted Bangladesh ever since its birth in 1971. The two parties treat each other as mortal enemies and display a deeply ingrained culture of revenge politics. This inhibits a robust and sustained commitment to peaceful transfer of power. Professional politicians, regardless of their affiliations, come from a toxic gene pool representing a mix of ideologues, opportunists, crooks and criminals. Whether a genuinely third political force can emerge from the youth-led movement remains an open question.