A modern central bank usually relies on ‘monetary policy committees’ or MPCs (albeit with different names, such as boards and councils) that play a pivotal role in the conduct of monetary policy. The collective deliberations of the MPCs are held regularly throughout the year and are geared towards recommendations (either by vote or consensus) on the setting of the policy rate.

The core principle is that the practice of monetary policy – and hence the role of the MPCs – should be free of political pressure. Central banks should be accountable but have operational independence in pursuit of their primary goal of maintaining price stability.

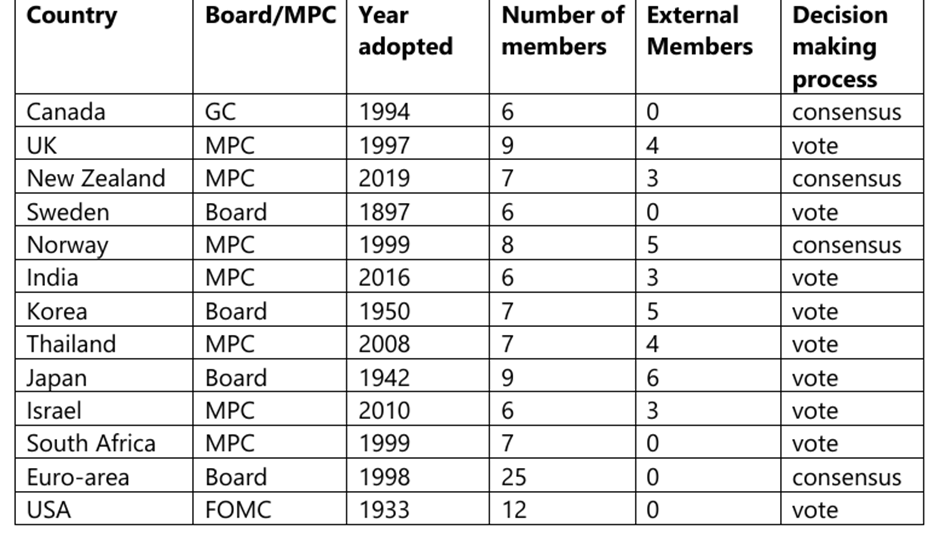

The size of the MPCs and the decision-making structure varies across countries and regions as shown below (Table 1). The MPCs are dominated by internal bank staff and economists, and, in some cases, with representatives from the corporate world. There are also cases in which there are no external members. There is no scope for representatives of workers and employers and representatives from civil society to be part of the membership of MPCs.

Table 1: Composition of MPCs, selected central banks

Source: https://rbareview.gov.au/sites/rbareview.gov.au/files/2023-04/rbareview-paper-gai.pdf

The degree of gender parity is low in a typical MPC. India is a conspicuous example – see Exhibit 1. Would improving gender parity improve the quality of monetary policy as measured in terms of maintaining price stability? Research findings on this are ambivalent, but the aim is to use an august institution to promote gender equality which is a core element of the global development agenda.

Despite the restrictions placed on central banks that restrain them from broad-based community-level engagement, these entities have tried to overcome such restraints by a transparent communications strategy in which deliberations of MPCs are made public. Furthermore, in recent years central banks have moved away from a preoccupation with price and financial stability. One important example of this trend is a new form of engagement via international cooperation among central banks, most notably supporting climate action as a key aspect of monetary policy. This is best illustrated by the ‘Network for Greening the Financial System’ (NGFS) which now has 134 members.

Financial inclusion is another way in which central banks are changing their engagement with workers and employers and the broader community. As is well known, the aim of financial inclusion is to incorporate the unbanked segment of the population – which can be quite large in developing countries – into the formal financial system. A 2024 meta-analytical assessment shows that ‘…financial inclusion outcomes reflect small, positive and statistically significant average effects on consumption, income, asset and other poverty-related indicators. Given this finding, it is noteworthy to point out that the ‘Alliance for Financial Inclusion’ reports that there are now 84 central banks across the world that have formally integrated financial inclusion in their mandates.

Financial inclusion creates synergies between monetary policy and poverty reduction strategies as well as the agenda of transition to formality. Central banks have discovered that financial inclusion, by encouraging formalization, improves the monetary transmission mechanism and thus strengthens the effectiveness of monetary policy. This in turn creates the space for workers and employers as well as civil society at the domestic level to engage with monetary authorities in areas that go beyond price stability.