The ‘gilded age’ refers to a certain period of American history (most notably the 1870s) which was characterized by ‘a period of gross materialism and blatant political corruption’. The key actors of the gilded age were a cohort of robber barons. They have been described as

‘…the powerful 19th-century American industrialists and financiers who made fortunes by monopolizing huge industries through the formation of trusts, engaging in unethical business practices, exploiting workers, and paying little heed to their customers or competition…The robber barons …amassed their fortunes by monopolizing essential industries. In turn, these monopolies were built upon the liberal use of …intimidation, violence, corruption, conspiracies, and fraud.’

Sounds familiar? One could readily argue that this is an apt description of a handful of ultra-wealthy individuals, often called oligarchs, in 21st century Bangladesh. They also lived in the gilded age during the now-defunct Ancien Regime of Hasina. A leading Bangladeshi economist (Dr. Debapriya Bhattacharya) has observed:

‘Oligarchs are the wealthy people and politically powerful. And we did not see such groups in Bangladesh in the past the way we are witnessing now…’

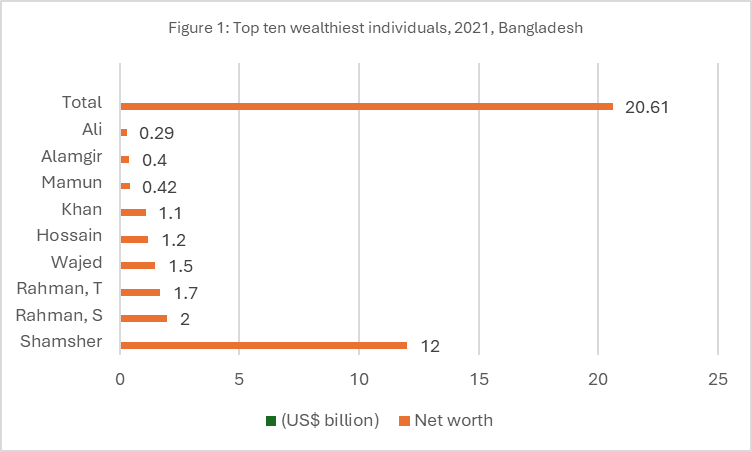

He declined to name them, but one can easily find such names through media reports. Figure 1 reveals pertinent details on the ten wealthiest individuals. Some have fallen on tough times after the downfall of the Hasina regime because they were so closely associated with it. Others live abroad and are safe from the long arm of Bangladeshi law enforcement agencies for their alleged crimes and misdemeanours.

Source: Derived from Top 10 Billionaires in Bangladesh 2024 | Meet the Richest Titans from Bangladesh | Business Haunt

On top of the ten richest individuals identified above, one of the latest editions of the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report estimates that, in 2021, there were 28,931 USD dollar millionaires in Bangladesh with an average net worth of US$ 3 million. If this group is added to the ten richest individuals identified above, one arrives at an aggregate net worth of US$ 107.4 billion. While this reads like a lot, standard measures of wealth inequality express the collective net worth of the wealthiest individuals in a country as a share of the aggregate wealth of a country. This turns out to be 12.9 %. Is this high or low relative to the past and relative to other countries?

This is where the world inequality database becomes extremely useful. It has been developed by a world class team of scholars working in the field of inequality. This team measures inequality in terms of the wealth share of the top 1% of the richest in a country. Using this method, one arrives at the evolution of wealth inequality in Bangladesh between 1995 and 2022. This is shown in Figure 2. Contrary to widespread belief, wealth inequality in Bangladesh has been falling moderately since 2005, after rising between 2000 and 2005. In particular, the idea that the thoroughly discredited Hasina regime was associated with rising wealth inequality does not seem to be compatible with the available evidence.

Figure 2

How does Bangladesh compare vis-à-vis other countries? Here too, there are some surprises. Compared with a selected group of middle-income countries (Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa), wealth inequality in Bangladesh (as recorded in 2022) seems noticeably low.

Source: Derived from world inequality database

Some caveats are in order. It is entirely possible that the degree of understatement of net worth in Bangladesh is higher than in other comparable countries due to tax evasion and money laundering. It is equally possible that the impact of such factors has increased over time leading to a spurious reduction in wealth disparities. Clearly, a lot more research needs to be done to explore and examine these critical issues so that one can sift rhetoric from reality. What one can at least say is that several individuals and business groups drew on their close political connections to acquire a great deal of wealth under the Hasina regime and thus behaved like the robber barons of 19th century America.