By

Aunul Islam, PhD (Imperial College, UK)

Synopsis:

This is a deeply personal narrative yet layered with history. What stands out is how the narrative intertwines individual memory with collective national trauma. The author moves between moments of hope (1971, independence) and disillusionment (1975, the assassination of Bangabandhu, and later political upheavals), showing how “paradise” shifts from a homeland to a fragile state of mind.

In Bangladesh, memory serves both as a unifying force and a source of division

Paradise. For me, it was never a distant dream—it was home. The land where rivers meandered through green fields, where the air carried the scent of liberation and hope. In 1972, at sixteen, I left that paradise behind, boarding a plane to the United Kingdom with a heart full of ambition and a mind still echoing the cries of victory from a bloody war of independence. Bangladesh was free, and I believed its future would be bright.

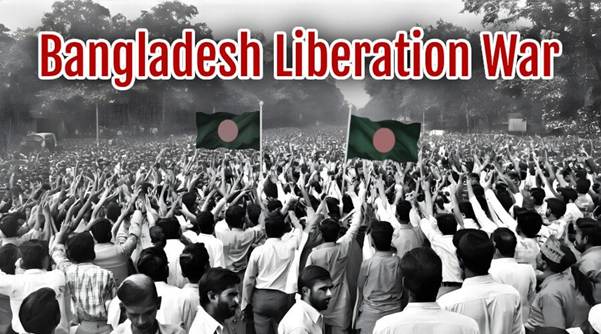

Image 1: A huge crowd celebrates the Bangladesh Liberation War

Three years later, I returned. The contrast with Britain was stark, yet I felt no dissonance. My country was poor, scarred by war, but it was mine until 15 August 1975, when paradise bled again. The Father of the Nation—our beacon of freedom—was brutally murdered along with his family in a military coup. What shattered me was not only the violence but the silence that followed. A nation that had fought so fiercely for liberty now stood mute, whether paralysed by shock or poisoned by betrayal. My dream of returning home after my education crumbled that day.

Image 2: The dark night of Bangabandhu’s assassination: how it unfolded…bdnews24.com, 15 August 2021

I tried again in 1979, hoping time would heal. But the spirit of the liberation war was fading, replaced by whispers of corruption and compromise. In 1985, I returned to settle, married, clinging to the hope that roots could still grow. Yet the soil felt strange beneath my feet. By 1988, I went back to my newly adopted paradise—the UK—carrying the ache of a homeland slipping away.

From 1995 to 2006, I made another attempt. I walked the streets of my childhood, searching for the rhythm I once knew. But the society had changed beyond recognition. The ideals we fought for were eroding; the language of freedom was drowned in the noise of greed and power. I was a stranger among my own people.

And then came the final blow. From 2006 to 2025, I watched from afar as history was rewritten. In 2024, another political upheaval erased the very memory of our liberation struggle—the foundation of our identity. The dream that had carried me across oceans was gone. My paradise was not just lost; it was betrayed.

Image 3: Celebrating the July uprising…but where is the nation heading?

Image 4: Bangabandhu Sheik Mujib’s home is destroyed as a crowd watches with a combination of fear and fascination

What does it mean to lose paradise? For me, it is not the loss of land or flag, but the slow death of ideals—the erosion of truth, justice, and memory. I fought for a country that promised freedom, dignity, and hope. Today, that promise lies buried beneath the weight of power and silence. Paradise, I have learned, is not a place. It is a state of mind—a fragile vision we carry within us. And when that vision dies, even home becomes foreign.

I am a migrant twice over—once by choice, and now by necessity. My adopted land gave me shelter, but my heart still wanders the streets of a homeland that exists only in memory. I am, and will remain, a stranger in my own paradise.